Part of a five-foot-long jawbone of an extinct whale was recently discovered by UGA researchers diving about 20 miles off Georgia’s coast.

The bone dates back 36,000 years, to a time when gray whales were populous on both coasts of the U.S. and Europe. Today the Atlantic gray whale is gone, but the mammals are still found off the western seaboard.

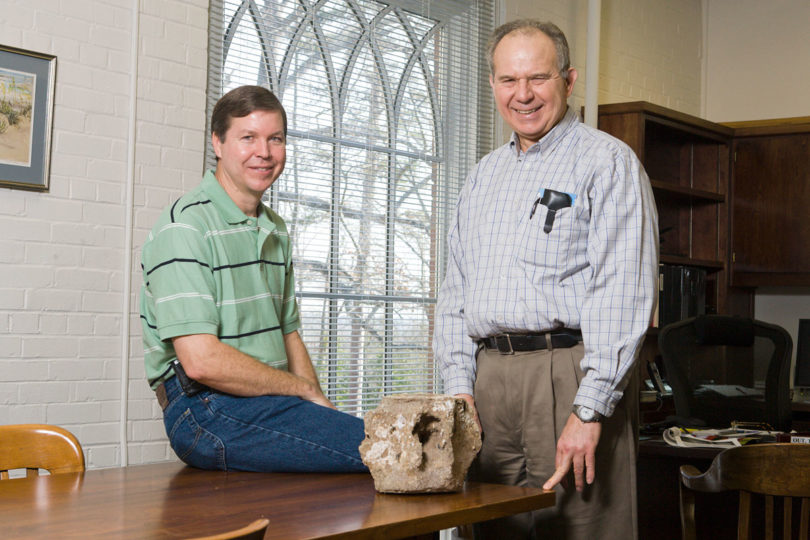

The discovery, which is the oldest found fossil of the gray whale, happened completely by accident, according to Scott Noakes, an assistant research scientist in UGA’s Center for Applied Isotope Studies.

“Finding whale bones was not what we set out to do,” he said. “It’s just something we fell into and had to learn a lot about.”

Noakes and other researchers from UGA were studying erosion in JY Reef, which is just 10 miles north of Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary off Sapelo Island. The reefs, while close to each other, are structurally distinct. JY is made of thousands of cold-water scallop shells, which are slowly eroding.

As the reef erodes, various items trapped inside began to emerge. This is how Noakes noticed a peculiar looking protuberance jutting out amidst the reef about 60 feet beneath the sea surface.

“This whole area used to be dry land during the Ice Age, so we originally thought it might be the mandible to a mammoth,” Noakes said. “But as we got more into it, the possibility that it was a marine mammal began to develop.”

Once the bone was found, the crew, along with members from Georgia Tech, Georgia Southern University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, began a two-year process to bring the bone to dry land.

Once the bone was excavated, the crew took snapshots and began to circulate the pictures on the Internet. One landed on the screen of James Mead, a mammal curator at the Smithsonian Institution, who declared within minutes that it was the mandible of an Atlantic gray whale—an animal that has not been heard of since the 1700s.

Erv Garrison, the academic department head of anthropology at UGA, helped excavate the bone. Everywhere he went, he said, people got excited.

“I’ve never dealt with much buzz before, but there was a buzz about this,” he said.

A colleague at McMasters University in Canada took a bit of the discovery and began searching for ways to extract DNA out of the ancient bone.

The extinction of the Atlantic gray whale can be traced back to three factors: its friendly nature, its habit of eating close to shore and its blubber.

In fact, the only way scientists know that Atlantic grays ever existed was from information gathered from seaman’s logs and the fossil record. There is no true scientific account of the creatures in their natural habitat.

“Since it’s a coastal whale, they were easy to capture and haul onto shore, instead of having to bring them aboard a boat out at sea,” Noakes said. “And they had a high-oil yield, which made them valuable.”

Pacific gray whales, however, were saved from a similar fate after finding their way onto the Endangered Species list in the 1940s. Thanks to conservation efforts, however, they were removed from the list in 1995.

However hopeful, that story is not the norm. The right whale, a relative of the gray, is facing a crisis.

“We’re hoping that this find can bring more attention to right whales so that they won’t face the same fate,” Noakes said.